The ‘Battle of Lewisham’ was a confrontation in London on 13 August 1977, resulting from a National Front march through multi-racial Lewisham, which the Metropolitan Police facilitated. Most of the local community opposed the march, as did left-wing parties, trade unionists, and anti-racist groups.

The subsequent violence, mainly between counter-protesters and the police, saw the first use of riot shields on mainland Britain and mounted police and baton charges, marking a shift by the Metropolitan police towards more aggressive tactics.

At least nine Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) undercovers reported on the parties and organisations involved in the events at Lewisham. Six of these have been identified, whilst three remain unknown.

Those known undercovers were HN13 'Desmond ('Barry') Loader' , HN356/HN124 ‘Bill Biggs’ , HN354 Vincent Harvey (‘Vince Miller’) , HN80 ‘Colin Clark’ , HN303 ‘Peter Collins’ and HN353 ‘Gary Roberts’. The three unidentified undercover officers also provided statements in the Closed Officer Evidence.

However, despite this coverage, the SDS undercovers, Special Branch, and A8, the department of the Metropolitan Police tasked with organising the policing of large protests, underestimated the scale and intensity of the local community's response to both the NF march and the policing operation.

Part 1 of this article provides a brief history of the precursors and the events in Lewisham on 13 August 1977.

Part 2 analyses the role of the SDS undercovers in gathering intelligence from groups planning the event they had infiltrated.

Part 2 also considers whether this information had a bearing on the proposal to ban the NF demonstration, or for planning the routes of the march and counter-protest. The disclosure from the Inquiry, enables fresh perspective to be added to the previously established account. Finally, it evaluates the actions of SDS undercovers on the day and their influence on the events on 13 August 1977.

The rise of the National Front

The National Front (NF) had been in existence since 1967, its fortunes over the succeeding decade waxing and waning, partly down to infighting between the various ‘empire loyalist’, fascist and neo-Nazi groups and leaders of which it was composed. These factions did agree on some basic principles, anti-communism, the halting of immigration and the repatriation of non-white migrants.

The NF achieved some popular traction around the issue of immigration in the early 1970s, particularly over the arrival of Asian refugees from African ex-colonies. By the mid-70s, the NF had linked their anti-migrant stance with economic and urban ‘crises’, blaming non-white residents for unemployment, poor living conditions, and rising crime.

In the May 1977 elections for the Greater London Council, the NF and its recent splinter, the National Party (NP), polled over 125,000 votes, placing them as the fourth and fifth most popular parties in the capital, respectively. This increase in the share of the overall vote for the two fascist parties obscured more definitive local trends.

In Deptford, in the southeast London borough of Lewisham, in a byelection, the Labour candidate had won the previous May with 43.5 per cent of the turnout, one per cent less than the combined votes of the NF and NP candidates.

ALCARAF and the Lewisham 21

The rise in support for the two openly racist parties, particularly in Deptford, led to the formation in 1976 of the All Lewisham Campaign Against Racism And Fascism (ALCARAF) , a broad coalition of community groups, churches, trade unions and political parties, including the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). Amongst its leading figures were the Bishop of Southwark and the Mayor of Lewisham.

The following year, ALCARAF affiliated to the Anti-Racist Anti-Fascist Co-ordinating Committee (ARAFCC), a wider coalition of anti-fascist, women’s and Black groups from across London.

1976 also saw the re-emergence of a racialised, media-led ‘moral panic’ concerning mugging and street crime in London, which suited the political agenda being set by the NF. In the early hours of the morning of 30 May 1977, the Metropolitan police undertook a series of coordinated raids on 20 households in Deptford and Lewisham.

Around 60 people were arrested, of whom 21, who were all of African-Caribbean descent, were controversially charged with conspiring to commit robbery.

Shortly after the court hearings, a community campaign, the Lewisham 21 Defence Committee (LDC), was launched to protest the charges and the treatment of the arrestees. The LDC began to organise public meetings on Lewisham High Street (Figure 1, Location 3):

This activity galvanised the local National Front, which began to organise paramilitary-style attacks on the meetings in order to break them up. One relatively small march by the Lewisham 21 Defence Committee [2 July 1977] was attacked by 200 NF skinheads, leading to over eighty arrests. The fascists also began to attack socialist paper-sellers on a daily basis, embarked on a terror campaign against black and Indian shopkeepers, vandalised a local Sikh temple, and firebombed the local offices of Trotskyist group Militant Tendency.

To march or not to march?

It was in this context that the NF leadership announced a national callout, stating they would march from Deptford (Figure 1, Location 2) to Lewisham on Saturday, 13 August, under the banner ‘Drive the Muggers off the streets’. NF organiser Martin Webster claimed this would be their ‘biggest ever rally’ and, in a pre-march press conference, stated the NF intended to ‘destroy race relations’ in Lewisham.

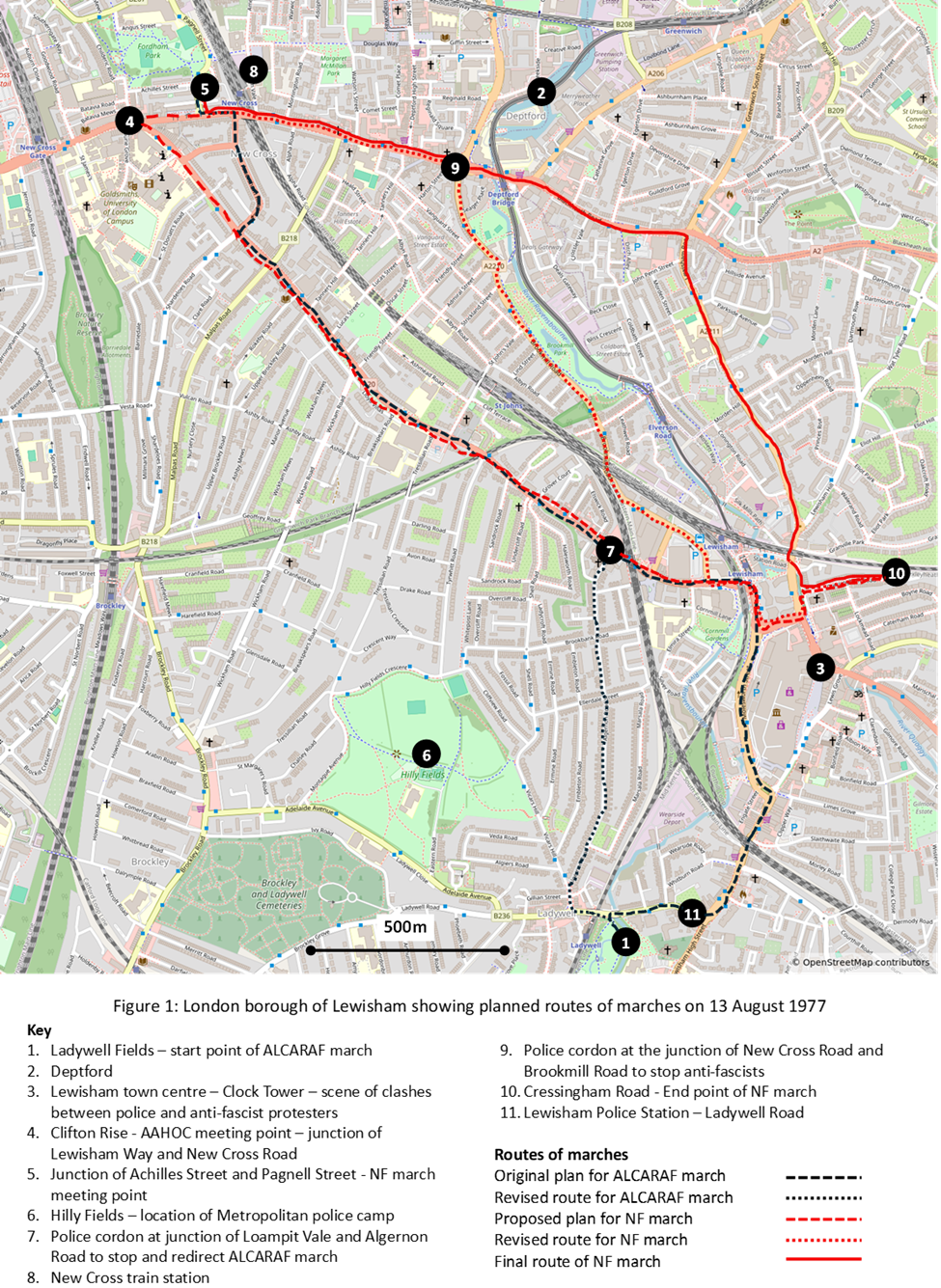

ALCARAF reacted to this news by planning their own counterdemonstration and approached ARAFCC for support. They also met with local police and agreed on plans for a rally in Ladywell Fields in Lewisham (Figure 1, Location 1), followed by a march to Deptford. This was planned to take place in the morning, before the NF march began in the early afternoon.

ALCARAF, along with local politicians and a delegation of Labour MPs, also began lobbying Labour Home Secretary Merlyn Rees and Metropolitan Police Commissioner David McNee to ban the NF march using his powers under the Public Order Act 1936. Such a ban was not unprecedented. The previous year, the risk of violence at a proposed NF rally had led to the organisation being stopped from using Trafalgar Square in central London.

However, McNee refused to comply, so Lewisham Council applied to the High Court to compel him to request a three-month temporary ban on all marches in the borough. Despite the increasing threat of violent clashes, McNee pledged in an affidavit that ‘my powers are sufficient to enable me to prevent serious public disorder’. The legal challenge failed on 11 August, two days before the planned marches were to go ahead.

Whilst ALCARAF were pursuing their lobbying and legal attempts to block the NF march, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) , International Marxist Group (IMG) and Communist Party of England (Marxist-Leninist) (CPE-ML) and other left-wing groups formed an umbrella organisation, the August 13th Ad Hoc Organising Committee (AAHOC). The AAHOC planned to stop the NF march from leaving New Cross and were supported by elements of ARAFCC.

The AAHOC decided that the key location to block the march was the intersection of Lewisham Way and New Cross Road, close to the NF meeting point at the rear of New Cross station (Figure 1 Locations 5 and 8) . This site was chosen, as Lewisham Way was the most direct route into Lewisham itself. The meeting point selected for the anti-fascists was Clifton Rise, a side street off New Cross Road (Figure 1, Location 4). This location was disseminated through the various antifascist organisations, largely by word of mouth.

On 2 August, Commissioner McNee intervened, overruling the route of the ALCARAF march that had been agreed with the organisers and the local police. Instead, the new circular route kept the marchers far away from New Cross, within Lewisham, starting and ending at Ladywell Fields (Figure 1). This was controversial as the NF were being allowed by McNee to march from New Cross through the centre of Lewisham.

Essentially, it appeared the ‘peaceful’ ALCARAF march was being undermined or even sidelined to facilitate the NF. Despite this setback, ALCARAF decided to continue following the route originally agreed with local police.

In preparation for the operation planned for Saturday, 13 August 1977, the Metropolitan police set up camp in a series of large marquees on Hilly Fields (Figure 1, Location 6), a park close to Ladywell Fields. It was a major policing effort, involving more than 2,600 police officers, 48 of whom were mounted, and with an operational control room at Scotland Yard.

The Special Patrol Group (SPG), a supposedly 'elite' unit of police officers created to combat serious public disorder, had already developed a fearsome reputation for violence during the Grunwick dispute in June and July 1977. The SPG was somewhat ominously deployed in the Clifton Rise area to ‘look after’ the ‘left-wing’.

Saturday 13 August 1977

In the early hours of the morning of 13 August, the home of the chief steward of ALCARAF was attacked by fascists who broke the windows. Later that morning, a police unit raided an empty house opposite Clifton Rise based on intelligence that the SWP were going to occupy it in preparation for the day ahead.

At 11.00-11.30 am, around 5,000 people gathered in Ladywell Fields for a rally with speeches by the leaders of ALCARAF, including the Mayor of Lewisham and the Bishop of Southwark. At midday, led by the Mayor and the Bishop, the march formed up and made its way along Lewisham High Street before being halted by a police cordon on Loampit Vale (Figure 1, location 7), the route to New Cross and Deptford.

At this point a senior police officer attempted to direct the march back to Ladywood Fields along McNee’s revised route, despite the protests of the Bishop and the Mayor. As they had previously agreed, if this situation arose, the ALCARAF organisers ended the march on the spot and asked it to disperse.

About 1,500 people avoided the police cordon, making their way by side streets towards New Cross and the rally point at Clifton Rise. At around 1.30 pm, the crowd was joined at Clifton Rise by 800 members of other left-wing parties. A series of speeches was delivered by members of the IMG, SWP and Flame group , including two from the Lewisham 21 Defence Committee.

The speeches were interrupted at 2.00 pm by a large contingent of police led by mounted officers who attempted to disperse the anti-fascists. In response, smoke bombs and bricks were thrown at police, and hand-to-hand fighting broke out. The police intervention failed to clear the crowd.

At 2.00 pm, around 1,200 NF and NP supporters, including contingents from Leeds, Bristol, Birmingham, Sussex and Manchester, met at Surrey Docks station (Surrey Quays today) and travelled by the underground to New Cross Gate station, close to the start point of the march at the junction of Achilles Street and Pagnell Street.

At 3.00 pm, the NF, led by their ‘honour guard’ carrying Union flags on spiked poles, moved off down Pagnell Street protected by hundreds of police officers on either side and a contingent of mounted officers at their head. As soon as the marchers reached New Cross Road, they were attacked by the waiting crowd who threw a hail of missiles including bricks, bottles and wooden staves. Antifascists broke through the police lines and physically attacked the NF marchers.

The NF column was harassed from side streets for about 500m along New Cross Road until police set up a cordon at the junction of Deptford Broadway and Brookmill Street (Figure 1 Location 9). Clashes between the anti-fascists and police took place at the cordon, as the NF contingent was hurriedly led away by their police escort.

The ‘alternative route’ the police had previously agreed with NF leaders was based on a situation in which the anti-fascists succeeded in blocking Lewisham Way, the direct route to Lewisham from New Cross. As this was now the case, it had been planned for the NF march to follow a parallel route along Brookmill Road and Thurston Road and then, crucially, directly through Lewisham town centre (Figure 1).

However, when the police control room at Scotland Yard became aware that a crowd of antifascists and local youth was gathering in Lewisham by the Clock Tower, they decided to alter the route once again, this time avoiding the centre of Lewisham altogether. The march was redirected by police along Blackheath Road and Lewisham Road, ending at 4:00 pm in a car park at the end of Cressingham Road in the residential back streets of Lewisham (Figure 1, Location 10).

The leaders of the NF made hurried speeches from the back of a lorry to their estimated 2,000 supporters, before Webster advised them to disperse as quickly as possible because the ‘police were taking a hammering from the left-wing at the end of the road’. By 4.30 pm, the NF marchers had left, led by police through a tunnel in Granville Park and onto waiting trains at Lewisham station.

After the NF had been diverted away from Lewisham Way, the anti-fascists returned as planned to Lewisham and congregated at the Clock Tower. The crowd of around 4,000 people, made up of local youth and antifascist demonstrators, blocked and then attempted to barricade the High Street and Lee High Road in anticipation of the NF attempting to march through central Lewisham. Around 4.00 pm, some of the antifascists became aware that the NF march had been rerouted to nearby Cressingham Road. They attempted to ambush the rally from the side roads but were held back by police cordons.

Police then tried to disperse the crowd by force at the Clock Tower, pushing them southwards along Lewisham High Street towards Catford. Riot shields were deployed for the very first time in England. Crucially, no information was provided by police to counter-protesters that the NF march was over and they had dispersed. In the fighting that followed, police vehicles were damaged, and part of the crowd surrounded Lewisham Police Station on Ladywell Road (Figure 1 Location 11), attacking it with bricks and other missiles.

The departure of the NF and the increasing involvement of local youth led to the violence being solely directed at the police. By 5.00 pm, the fighting had largely petered out.

According to various estimates, 214 people were arrested during the ‘Battle of Lewisham’, at least 111 people were injured, along with 56 police officers, 11 of whom were hospitalised.

Lewisham ‘77

The ‘Battle of Lewisham’ on 13 August 1977, like the Grunwick dispute in the industrial sphere, is regarded as marking a sea-change in policing tactics on the British mainland between the 1970s and the 1980s. This assessment is supported by the importance given to the event in the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) annual report for 1977, which states:

Any review of public disorder during the past year must be dominated by two major events, i.e. the Grunwick dispute and the confrontation between the extreme left and right at Lewisham in August.

The Special Branch annual report reiterates this evaluation, but clearly places the internal security emphasis on the ‘extreme left’:

The internal threat to public order has come mainly from the organisations of the extreme left with the occasional incursion from their opponents at the opposite end of the spectrum. Both factions are under close scrutiny by the [Special] Branch.

A letter from Gilbert Kelland, the Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police to the Home Office in 1978, referred to the confrontations in Lewisham the previous year and stated:

[T]he intelligence supplied by the Special Demonstration Squad of the numbers and intent of the numerous revolutionary parties enabled the Uniform Branch to effectively and economically police some of the most violent disorder in recent times.

There are a number of claims made in these statements which bear further investigation.

The Special Demonstration Squad

The close involvement of the SWP in both the precursors to the ‘Battle of Lewisham’ and the events on the day placed Special Branch in a good position regarding intelligence gathering. Of the six known SDS undercovers who reported on Lewisham, three had penetrated SWP branches or committees: HN80 ‘Colin Clark’ (Seven Sisters) , HN354 Vincent Harvey (‘Vince Miller’) (Walthamstow and Outer East London district committee) and HN356/HN124 ‘Bill Biggs’ (Plumstead).

Two others, HN13 'Desmond ('Barry') Loader' had infiltrated the East London branch of the Maoist, CPE(ML) and HN353 ‘Gary Roberts’, the IMG in south-east London. Special Branch, via the SDS undercovers, was thus gathering information and experience from the three main organisations that made up the August 13th Ad Hoc Organising Committee (AAHOC).

The remaining known SDS undercover, HN303 ‘Peter Collins’ , had spent three years in the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) and during that time had been tasked by the party to infiltrate the far-right Legion of St George and the NF. Along with Collins, Loader, a member of the West London CARF, and Roberts, all had direct experience (and perhaps kudos) in dealing with the far right in their various organisations. Roberts was present at Ducketts Common in Haringey earlier that year on 23 April 1977, St George's Day, when members of the SWP and IMG opposed an NF march through Wood Green in north London.

Along with information coming from the AAHOC, the SDS also claimed to have infiltrated a series of anti-fascist organisations that played a part in events in Lewisham in 1977.

These included CARF branches in Haringey, Hackney, Southwark and, crucially, Lewisham with the penetration of ALCARAF. They are listed as groups in the SDS Annual Reports, but evidence of reporting on them is virtually absent in the Inquiry disclosure.

Special Branch and the National Front

The Special Branch annual report for 1977 claimed that far-right groups were, like the ‘extreme-left’, under ‘close scrutiny’. This is certainly questionable. There is no evidence that far-right organisations were penetrated by the SDS, and no SDS undercovers were assigned to the NF in 1977, but for 'Peter Collins' for the WRP.

Indeed, the relationship between Special Branch and the NF in 1977 appears open and relatively congenial. For example, a month or so before the ‘Battle of Lewisham’ on 8 July, a Detective Inspector (DI) from the Special Branch visited the headquarters of the NF in the affluent southwest London suburb of Teddington. He had a meeting with NF National Organiser Martin Webster in a side room, where they spoke alone; they clearly knew each other quite well. The officer reported:

At first, he was very reluctant to discuss this forthcoming march. I asked him to explain his attitude as he had previously fully co-operated with me over public order issues.

Webster then said that the NF were unhappy about the number of their members arrested the previous Saturday in New Cross. The officer reported back that until the cases following these arrests were dealt with:

There is little doubt that [...] the amount of co-operation police will receive from the National Front regarding their proposed activities will be negligible.

This ‘co-operation’ between Special Branch and the NF, or recent lack of it, is referred to in several documents (see for example,'minutesheet concerning Lewisham' ), as is the relationship of trust between the organisations that is alluded to by Metropolitan Police Commissioner McNee when he stated that:

Experience has shown that most organisations do not depart from a route which has been agreed with my officers and this has proved to be so in the past with regard to the National Front.

Instead, Special Branch superiors were clear that the ‘central problem with the 13 August [in Lewisham] is not the ALCARF [ALCARAF] march but the antics of the ultra-left’.

Bans and routes

The friendly relationship between Special Branch, Commissioner McNee and the NF leadership was also reflected in determining the routes of each march and whether the NF march should be banned. In a strategy meeting on 27 July between Special Branch and A8, responsible for the policing of the protests, a Special Branch officer opened with the statement:

The NF supporters were in a determined mood and would not willingly accept any arrangement whereby they were not allowed to parade through the main shopping area of Lewisham.

This intransigence framed the rest of the meeting, with those present questioning the ‘purpose of the ALCARAF [counter] demonstration’, proposing it should be rerouted and the start time altered to suit the requirements of the NF march.

At no point was there a suggestion that the NF march should be routed away from Lewisham town centre.

The meeting was then informed that a delegation from ALCARAF, along with Health Minister John Silkin and the MP for Lewisham, had visited A8 to request that the NF march be banned. The response of those present was to discuss the reactions to such a ban by right or left wing ‘extremists’, rather than considering the wishes of ALCARAF and the multi-racial community in Lewisham.

The Special Branch officers present gave a simple assessment that a ban would be more damaging to the NF and would be welcomed by the left-wing. This controversial claim led the meeting to propose that the police should resist a ban, stating that this was a ‘political decision’.

The recommendations from this meeting on the routes and timings of marches, as well as a potential ban, appear to have guided the decisions made by A8 and Commissioner McNee over the following two weeks. After local police had already agreed to the route of the ALCARAF demonstration, A8 then stepped in and rerouted it away from New Cross. This decision was clearly made to facilitate the NF march.

A ban on the NF march was resisted by the Commissioner and finally rejected in court, with McNee stating in an affidavit:

I am satisfied in the light of the information made available to - me by my senior officers that the police are able to maintain control of the situation and to prevent any serious disorder occurring.

This was a surprising statement, considering the volume of information supplied by SDS undercovers. This warned that there would be a large turnout of the ‘extreme left’, that they were planning to stop the NF march before it left New Cross, and that violent clashes were therefore very likely.

This is reflected in the retrospective statement made by SDS undercover HN354 Vincent Harvey (‘Vince Miller’):

I think several of us [SDS undercovers] were amazed that having given the information we gave, and pointing out that if they [the NF] went a different route, they would bypass an awful lot of the planned confrontation and could still have … [made] their point and then there would have still been confrontation but it would not have been as organised and planned. A couple of us had suggested [the NF] just go a different route. And all such information was completely ignored. It was as if we hadn't put any information in at all.

Or as one participant, 'Madeleine' perceived the decision:

Because when you think about it […] their [NF] anti-mugging march that they called wasn't in the West End, it was a deliberate provocation; it was an act of violence against the community itself. It was determined to go through an area of, you know, high immigration, where it was already like a tinderbox ... And allowing that march to go ahead […] effectively the police struck the match and threw it, and watched the whole thing blow up.

Despite McNee's assurances that the Metropolitan Police could deal with any confrontation, by 13 August A8 had already been forced to reroute the NF march eastwards along New Cross Road, away from Lewisham Way. This was because of the increasing threat from leftist groups.

On the day, A8 were compelled to reroute the march once again, this time away from the centre of Lewisham altogether, after the (predicted) serious violence at Clifton Rise and the presence of the crowd that had gathered at the Clock Tower in the centre of Lewisham.

This begs the question of why, based on the SDS evidence in the lead-up to the ‘Battle of Lewisham', Special Branch and A8 did not advise their superiors to alter the route of the NF march in the first place. Or at least why their superiors, such as Commissioner McNee, failed to listen and seemed determined to facilitate the NF march through central Lewisham, come what may. After all, McNee and A8 seemed to have little issue with altering the route of the ALCARAF march.

Preparations and on the day…

In the weeks leading up to the events in Lewisham, Special Branch (and, by default, A8) received a large amount of information from SDS undercovers regarding the potential number of attendees and the tactics of political groups within ALCARAF and the AAHOC. One SDS undercover, Vincent Harvey, even attended a meeting of SWP stewards on 12 August, the day before the events in Lewisham.

Harvey claimed he was tasked with organising the stashing of piles of bricks along New Cross Road near Clifton Rise, though this was disputed by the participant witness, ‘Madeleine’. Harvey and ‘Bill Biggs’ also reported on the creation of ‘protection squads’ by SWP branches, groups of six ‘heavies’, to be deployed against the NF.

This tactical information probably influenced the planning for the policing operation in terms of commitment of the SPG, number of officers in general, and the deployment of mounted police. Intelligence that the locus of the policing effort should be on New Cross Road, close to Clifton Rise, proved to be correct. However, the SDS, Special Branch, and A8 clearly underestimated the scale and intensity of the local community's response to both the NF march and the policing operation.

On the day itself in Lewisham, there were 18 Special Branch officers on the ground, including the known and unknown SDS officers listed in this article.

Despite this, the ability of Special Branch officers to influence the outcome of the events once the action had started was very limited. SDS undercovers supplied information to Special Branch/A8 about an empty house opposite Clifton Rise that was going to be occupied the night before by SWP members in preparation for the clashes the following day.

This led to a police raid on the morning of 13 August. It is telling that this relatively minor achievement made it into the annual report of the SDS for 1977. Other than this, the evidence of SDS undercover influence during the events of 13 August is fairly thin.

One area where Special Branch made a significant intelligence effort was collating information on organisations and individuals present in Lewisham on 13 August 1977. A list of over 100 banners representing organisations as diverse as Christian Aid and the Anarchist Black Cross was collected principally from surveillance of the ALCARAF march.

Similarly, 14 pages of redacted names of ‘anti-fascist demonstrators’ who were present in Lewisham, noting if they were arrested or not, make up another Appendix to a Special Branch report. Similar, though far less extensive details were collated for those attending the NF march.