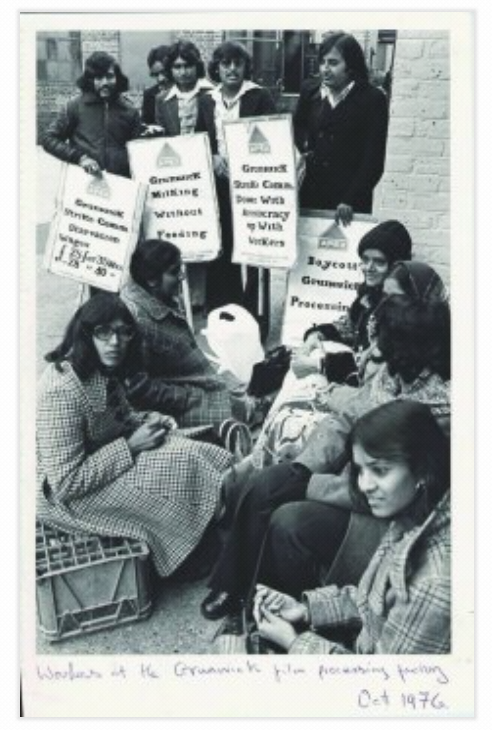

The strike by workers at the Grunwick film processing plants in northwest London, which lasted from August 1976 to July 1978, was exceptional for several reasons.

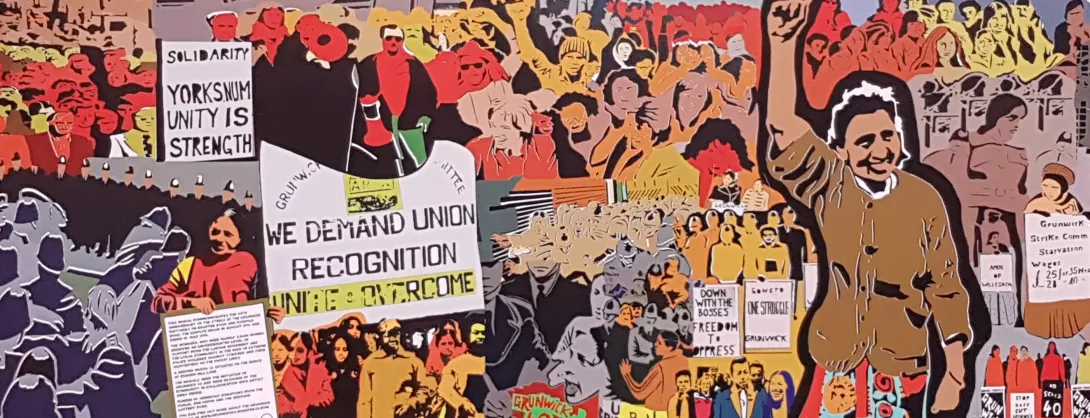

First, the strikers were predominantly migrant women and men of south Asian descent. Second, the strikers experienced widespread solidarity from members of many trade unions across the country and mass support across left-wing parties. Third, the dispute became well known to the general public and was framed in the media as not just a violent physical struggle between pickets and police on the streets, but also an ideological battle between employers' freedoms and workers' right to unionise.

Finally, Grunwick marked a shift in policing tactics in industrial disputes, moving from the defensive to the offensive, and significantly increasing the levels of organised force used. The success of these tactics relied, to varying degrees, on pre-event intelligence gathered by undercover police officers and information gleaned from their attendance at the mass pickets.

At least eight Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) Undercover Officers (undercovers) reported on the strike; five of these have been identified, whilst three remain unknown. Those known were HN296 ‘Geoff Wallace’, HN354 Vincent Harvey (‘Vince Miller’) , HN80 ‘Colin Clark’ , HN304 ‘Graham Coates’ and HN126 ‘Paul Gray’.

In addition, there is evidence that Special Branch deployed non-SDS undercovers to the Grunwick picket lines, such as HN474 Wilf Knight, who claimed he attended Grunwick as a Special Branch officer and may have been working for the Industrial section.

Two other Metropolitan Police officers, John Cracknell and HN1742 Anthony Speed , worked for A8 (public order) organising the policing of mass political protests, and provided evidence of interactions with Special Branch. The latter was an A8 planning officer directly involved in the policing at Grunwick.

This article will outline the history of the Grunwick dispute, analyse the role of the SDS undercovers and Special Branch in gathering information about the strike from groups they had infiltrated and consider how this information was used, particularly in relation to the policing of the dispute and the actions of the management of the Grunwick factories.

The strike begins…

The Grunwick film processing laboratories in Willesden, in the London borough of Brent, employed 500 workers who developed and printed colour film by mail order. The business offered a fast turnaround, which put pressure on its workers, especially during the peak summer period.

Consequently, the company took on temporary workers, enforced compulsory overtime and pushed the workforce to increase productivity. This often descended into bullying and threats of summary dismissal. Over a few years, in order to reduce wages, the company replaced most of its white female employees, recruiting lower paid south Asian women, many of whom were migrants.

On 20 August 1976, Devshi Bhudia was summarily dismissed from Grunwick for not working fast enough. Bhudia and several temporary workers walked out and began protesting outside the factory gates. The same afternoon, after an altercation with a director, Jayaben Desai, who had worked at Grunwick for two years, and her son walked out, meeting the other discontented workers at the gates. Over the next few days, 132 employees joined them, demanding ‘a union to represent them in negotiation with the management’.

The strikers joined the Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff (APEX) and were assisted by the local Brent Trades Council (BTC). BTC helped set up the Grunwick strike committee (GSC) and provided the nearby Trades Hall as a base for the strikers.

The managing director of Grunwick, Anglo-Indian George Ward, had already successfully resisted two attempts to unionise workers at the plant. Ward responded to the mass walkout by offering reinstatement to the strikers if they gave up their demand for union representation, which they rejected.

On 31 August 1976, APEX declared the strike official, and the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS), an independent body tasked with resolving industrial disputes, contacted Grunwick’s management. Ward refused to deal with either APEX or ACAS and dismissed all the striking workers. APEX approached the Trades Union Congress (TUC) for help, and they encouraged trade unions to support the strike through secondary action.

In November, the Union of Postal Workers (UPW) at Cricklewood voted to stop handling all Grunwick’s mail, a massive blow to the company, which could have handed a quick victory to the strikers. However, Ward responded by teaming up with the ultra-right wing National Association for Freedom (NAFF) and backed by the local MP and right-wing of the Conservative Party, threatened legal action, first against the UPW, who agreed to halt their boycott and then against ACAS, who had recommended the recognition of APEX by Grunwick.

Mass picketing

As legal battles were waged in late 1976 and into 1977, the GSC travelled the country, visiting workplaces and unions. The level of support they received gave the GSC confidence to call for mass picketing, which was planned to start on 13 June. The call was also registered by left-wing parties, who encouraged their members to attend—the mass pickets aimed to shut down Grunwick, thereby pressurising Ward into recognising APEX. The GSC also hoped this would propel the strike into the national news.

The first mass picket on 13 June was designated as ‘women’s only’, attracting about 700 people. This did not restrain the police, who used significant force to keep Grunwick open, injuring several women and arresting 84 people. By the end of the week, over 150 people had been detained, bringing the total to around 90 arrested over the previous months.

That week saw the deployment of the Special Patrol Group (SPG), a supposedly 'elite' unit of the Metropolitan Police created to combat serious public disorder, crime, and terrorism. The unit had operational independence, was nicknamed ‘the Cowboys’ by the Metropolitan Police and often arrived on duty to the 'The Dam Busters' tune. It was the first time the SPG had been deployed in an industrial dispute. The violent tactics of the unit were first reported at an APEX press conference on 22 June, led by two women who had been badly injured.

The mass picketing continued, culminating on 11 July with a ‘day of action’. This attracted between 14,000 and 18,000 supporters, including 3,000 miners. Around 3,700 police, including the SPG and 35 mounted officers, were also deployed. The strikers led a march of trade unionists and supporters from Roundwood Park, passing the two plants. Earlier that morning, attempts to breach the police cordons to blockade the gates of the Grunwick plants largely failed. By the end of the day, 123 police officers had been injured, and there were 65 arrests.

A week previously, the Cricklewood branch of the UPW had reestablished their boycott of Grunwick’s mail. Grunwick’s management responded to this potential threat with a secret operation organised and undertaken by 25 NAFF volunteers. Operation ‘Pony Express,’ shifted a backlog of 100,000 packets of the company’s mail in a lorry on the night of 9 July, two days prior to the mass picket.

Grunwick and the Labour government

The importance of the Grunwick strike to the Labour government should not be underestimated. The introduction of mass picketing in June 1977, the violence unleashed by the SPG and demonstrators on the streets of northwest London and the attendant headlines in the mainstream media all served to enhance the feeling of political instability. Prime Minister Callaghan was protecting a tiny majority of three seats in the House of Commons, and was so concerned about Grunwick:

that he even asked the cabinet secretary to draw up a note reminding him of the lessons of the so-called battle of Saltley Gates in Birmingham, when flying mass pickets won a decisive victory during the 1972 miners' strike and helped to bring down Edward Heath's Conservative government.

The appearance and arrest of Scargill and NUM officials at the mass picket at Grunwick on 23 June enhanced Callaghan’s fears, and he privately decided ‘the determining issue [at Grunwick] was now that of public order’, rather than a resolution of the strike. In a meeting at Chequers on 26 June Callaghan encouraged the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, David McNee, to reconsider his tactics, with the Home Secretary suggesting banning mass pickets and restricting access to the Grunwick plants.

Callaghan’s focus and that of Special Branch now turned to the activities of Scargill and the NUM, in particular, the information they had received of the approaching ‘National Day of Action’ at Grunwick on 11 July. A Special Branch report stated:

At the moment it seems feasible that this [the ‘National Day of Action’] could develop into one of the largest and potentially violent demonstrations ever seen in this country.

It was at this point that the Cabinet switched its emphasis from public order and the policing of Grunwick to a new approach that appeared to offer the strikers and the trade unions a carrot. On 30 June, the establishment of an inquiry tasked with finding out the causes of the Grunwick strike, chaired by Lord Scarman, was announced by the Secretary of State for Employment.

It appears that the real aim of launching the inquiry was to undermine the upcoming ‘National Day of Action’ on 11 July and buy some time for the government. The inquiry was accepted by APEX officials and was used to placate other trade union leaderships via the intervention of Len Murray and the TUC. In mid-July, the inquiry was cited by APEX as a reason to suspend the mass picketing.

Scarman reported back in August, finding in favour of the strikers by recommending their reinstatement and suggesting the recognition of APEX by Ward. The Grunwick board rejected Scarman’s findings, and soon after, a ruling in the Lords upheld the company’s right not to recognise a union.

The end of the dispute

The situation was now desperate for the strikers; ACAS had been rendered ineffective by legal action, the findings of Scarman’s inquiry were not binding, and the TUC pledge of support was turning out to be merely rhetoric. After the halt on mass picketing due to the Scarman inquiry, the GSC found it difficult to regain momentum. They made one last significant effort, aptly named ‘the day of reckoning’, calling for a mass picket on 7 November 1977.

The day was marked by the aggressive actions of the SPG, with flying wedges of hundreds of officers violently breaking up crowds of pickets and assaulting those they arrested. Of the estimated 7,000-8,000 present, 243 pickets were injured by police, of which 12 had broken bones. The Metropolitan Police claimed that 100 police officers were injured and there were 114 arrests.

By the end of November 1977 the TUC, trade unions and left-wing parties had decided their main focus was to defeat the government’s pay restraint and Social Contract policies and they ‘weren’t really interested in diverting resources any more towards the [Grunwick] strikers.’ The remaining 50 strikers ended their struggle to gain union recognition at the Grunwick film processing laboratories on 14 July 1978.

In their heavily redacted annual report for 1977, Special Branch makes a direct reference to the Grunwick strike, stating:

Whilst the extreme left campaigns against the Criminal Trespass Laws, the current regime in Chile, and hospital closures, have had little practical effect, they are in contrast to the massive publicity surrounding communist and Trotskyist involvement in the dispute at the Grunwick factory in Cricklewood, where a great deal of Special Branch effort was directed to the successful provision of forward intelligence.

The importance of Grunwick was also highlighted in the Special Demonstration Squad (SDS) annual report, which foregrounded the mass picketing as one of the two main public disorder events of the year, the other being the ‘Battle of Lewisham’ in August. Regarding Grunwick, the report states:

Throughout this dispute invaluable information was supplied by the SDS of last minute tactics and the numbers attending, the degree of violence anticipated, which enabled the uniform branch to effectively police one of the most violent and longstanding disputes for many years.

This assessment was backed up by a letter from Gilbert Kelland, the Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, to the Home Office asking for continuation of the SDS activities in 1978/79. Kelland claimed that at the Grunwick and Lewisham confrontations:

[T]he intelligence supplied by the Special Demonstration Squad of the numbers and intent of the numerous revolutionary parties enabled the Uniform Branch to effectively and economically police some of the most violent disorder in recent times.

Clearly, the positive claims made in these three sources were in the interest of the continuation of the SDS and thus may have been biased or exaggerated. It is thus worth reviewing the intelligence gathering on the Grunwick dispute by the SDS and Special Branch, its content, and how — and by whom— it was used.

The SDS and policing the mass picketing

The nature of the dispute at Grunwick was that it remained low-key for a considerable period of time before rapidly becoming the most serious public order event of 1977. There was little interest in the strike from the trade unions and left-wing parties or the mainstream media, politicians, police and the security services in 1976 or early 1977.

The call for mass support at daily pickets in June 1977 was the moment when this changed, and this is reflected in the intelligence reports that the SDS was gathering and passing on to Special Branch, from them to MI5 and the Home Office, and in some cases reaching the cabinet.

Information specifically useful for policing demonstrations was passed to A8, a department in the Metropolitan Police formed at the same time as the SDS in 1968. A8 was responsible for organising the policing for large-scale political events in London. This involved determining and obtaining the necessary police resources from the various divisions across the capital and organising the logistical requirements for these personnel.

A8 were also tasked with training the Metropolitan Police in controlling large-scale demonstrations. This was not a one-way transfer of intelligence; A8 officers were encouraged to contact Special Branch with specific requests for information or to obtain operational assessments, although they were largely unaware of the source of this intelligence or the existence of the SDS.

The policing operation at Grunwick over the summer of 1977 was organised by A8 from a control-room set up in a local school. The relentless nature of the day-to-day operation was described by Chief Inspector Anthony Speed, an A8 planning officer:

During the period of the Grunwick dispute, we would brief and plan for an operation the next day, get up at 3 am to get to Grunwick […] return after the disorder ended by about 10 am, and then plan for the following day.

The nature of the mass pickets at Grunwick was that the numbers attending each day varied, as Speed recounted:

Grunwick was also a daily issue, as it could go from a couple of dozen people in attendance to a couple of thousand people because of attendance from mining communities and Scargill.

Decisions over the daily commitment and content of policing resources were thus heavily reliant on up-to-date intelligence information:

Special Branch would give us this information by updating their assessment if they thought we needed it; they were providing us with information on a daily basis, and if it was important they would give it to us immediately, in person.

Prior to the mass pickets, four SDS undercovers were spying on branches of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) which became engaged in supporting the Grunwick strikers, whilst another three remain unidentified.

HN296 ‘Geoff Wallace’ infiltrated the Hammersmith and Kensington branch in 1975. HN354 Vincent Harvey (‘Vince Miller’) infiltrated the Walthamstow branch in January 1977, became its treasurer in June and took a similar role in the Outer East London district committee in July.

HN80 ‘Colin Clark’ was gathering information in the Seven Sisters branch in May 1977, whilst HN304 ‘Graham Coates’ was briefly a member of the Hackney branch and latterly Croydon.

HN126 ‘Paul Gray’ was chosen by the SDS to specifically infiltrate the Cricklewood branch of the SWP in December 1977 because of continued picketing at nearby Grunwick.

All eight of the SDS undercovers were present at least one picket at Grunwick, with some officers attending numerous times over the summer and autumn of 1977.

The Grunwick strike first appears in SDS reports on 26 May 1977, when Wallace writes that mass picketing will begin on 13 June with a week of action and an attempt to occupy the factory. The undercover officer also notes that the visit of three cabinet ministers to the picket lines the previous week had brought the dispute into the public domain.

There are several more written and signed off SDS reports on Grunwick at the end of May, but then a gap over the month of June and most of July. This silence corresponds with the period of intense daily activity on the picket lines at Grunwick. It involved some undercover officers with vehicles picking up other left-wing party members and ferrying them to Willesden in the early hours and then taking part in the mass pickets throughout the morning.

Meetings on picket line tactics were ad hoc, taking place the evening before, on the way to Grunwick or during the event itself. The lack of written accounts of meetings in this period in the archives of the SDS may have been a result of the ‘real-time’ nature of information gathering and delivery to the senior SDS officers, which was mostly achieved through phone calls. There is also a question of whether they ever existed during this period.

As SDS undercover ‘Colin Clark’ put it: ‘the key thing was to get information to the local police in a very timely fashion’ and he noted that the normal Special Branch reporting formalities were dispensed with.

Identifying groups and individuals

At Grunwick, SDS undercovers were asked to supply Special Branch, and by default A8, with forward intelligence on the plans for mass pickets, the potential commitment of branches of trade unions and left-wing groups, the expected levels of violence and details of any tactics that might be employed.

At the pickets, Special Branch plainclothes officers were also asked to act as ‘spotters’ whose job was to identify: ‘who was associating and organising small bands of anarchists and left-wing people’.

This was complemented by the collation of extensive lists of the names of pickets and supporters, and the banners of participating union branches and groups, which were supplied to Special Branch.

It has since been claimed that this information, which was collected on a day-to-day basis during the mass pickets by Special Branch undercovers, was added to the ‘Special Branch index, its secret list of “subversives,” [that] contained approximately 30,000 names.’

The identification of particular individuals on the picket lines, strikers and members of the GSC, left-wing organisers and trade union leaders was not just for intelligence purposes; it allowed them to be targeted for arrest by the police.

Long-term observers of the mass pickets noticed that initially the arrests were fairly random, but over the summer of 1977, they became more selective, with individuals snatched out of crowds of pickets and their supporters.

For example, on 23 June, a significant section of the executive committee of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), including their leader Arthur Scargill, was arrested.

Evidence of the identification of individuals and groups on the mass pickets by SDS and Special Branch undercovers can also be found in a tranche of A8 reports covering the period 14-27 June 1977 that were released under a Freedom of Information request. The Inquiry did not disclose these reports, although they offer good examples of how the intelligence gathered by the SDS was put to use.

The sample of reports demonstrates that each day of the mass pickets, A8 produced a detailed, chronological report of the activities of the pickets, their supporters, and their policing at each gate of the two Grunwick plants. The reports contain descriptions of the numbers attending, their genders and ethnicity, the numbers of arrests, the types of offence, and the levels of violence.

They also name trade union leaders, spokespeople and stewards, Councillors and MPs and ‘well known personalities’.

The A8 daily reports also identify and describe groups such as ‘Socialist Workers’, ‘white youths wearing Marxist badges’ and ‘students’. Speeches by leading figures in the dispute are recounted and, in some cases, transcribed and there are regular descriptions of verbal interactions between the strikers, their union representatives and the police commanders.

It is clear that at least some of this information is coming from SDS and Special Branch sources who were present at the pickets and were transmitting this information to A8 on a day-to-day basis.

Spying on the Grunwick Strike Committee

Although there is clear evidence of infiltration by SDS undercovers of left-wing groups, such as the SWP, who were involved in the mass pickets at Grunwick, there are also indications of intelligence gathering concerning APEX, Brent Trades Council (BTC) and the Grunwick Strike Committee (GSC).

Several Special Branch reports refer to decisions made by these organisations. Indeed, the first substantiated warning of the mass pickets appears on 31 May 1977, in a Special Branch report stating that APEX and BTC were initiating the tactic on 13 June and the comment that:

Although it is realised that this may lead to confrontation with the police, those taking part are determined that anything or anyone will be stopped from entering or leaving the factory [Grunwick].

Internal discussions and decisions of the GSC are referred to in several Special Branch reports in the lead up to the ‘day of reckoning’ on 7 November 1977. These include reports on their collaboration with various unions, including the NUM, the turnout they were expecting at the mass picket and the exact numbers of leaflets and posters they had printed to publicise it.

The interim report also noted that the GSC had been travelling the country drumming up support and had been as far as Gwent, in south Wales, to involve steelworkers in the dispute. Potential tactics to be used by pickets at Grunwick were also discussed:

Various disruptive actions are being considered by the ultra left-wing, including organising short marches from several directions at the same time, which they hope will cause sufficient traffic congestion in the area to prevent the coach from moving; waiting until the lines of police have formed up in the approach roads and then sitting in the roadway at the extremity of the line in sufficient numbers that police strength will be denuded and the cordons of police will be reduced, so allowing the pickets to break through should the coach get that far. Another suggestion has been the use of school children under the auspices of the National Union of School Students to sit in front of the police lines until shortly before the coach arrives and then go and sit in the road.

The Special Branch interim report on the ‘day of reckoning’ was followed three days later by a further ‘special report’, which contained even more detailed information. This gave the exact numbers of coaches travelling from numerous locations around the country to transport supporters to Grunwick, and reported that the GSC had heavily canvassed workers in factories in northwest London.

There were several more references to potential tactics at Grunwick, including using plumbers and electricians to gain access to the factories to cut off supplies, for a group of Yorkshire miners to carry out surveillance and then sabotage the buses used to carry workers into the plant and for a planned assault on an SPG carrier.

It would be expected that the latter information, in particular, would have been kept secret within the GSC. This suggests that the GSC had been infiltrated by Special Branch in some manner and was also collecting relevant information regarding support for the Grunwick dispute from around the country. The answer to the former may lie in a statement made by Jack Dromey of the GSC in 2007:

I discovered after the [Grunwick] dispute, from good policemen who talked to me in the thirty years since, that I was bugged at home, that the trades and labour hall was bugged, that there was a period that, we were followed, some of us in the dispute, and also attempts were made to infiltrate the strike committee, so there was a high degree of surveillance.

The latter is supported by documentary evidence that Special Branch was receiving information from regional police forces concerning demonstrators travelling to London to join the Grunwick pickets and the plans of local miners in West Yorkshire.

Collusion with Grunwick directors and NAFF

Another difficult issue to untangle is how much A8, or its proxies such as the local police or SPG, fraternised and coordinated with Ward, the board of directors and NAFF at Grunwick to break the strike. If there was collusion, which is likely if A8 were to successfully organise policing the streets around the Grunwick plant, then the question is how far did this extend? Was strategic and tactical information derived from SDS reports being shared by A8 with Ward and even NAFF?

It was certainly in the interests of the Metropolitan Police at the time to obscure or at least distance themselves from any obvious collaboration, as it would strengthen the strikers and their supporters' argument that the state was in league with employers, rather than being merely an arbiter.

As St John notes, the daily A8 reports on Grunwick differ from Special Branch assessments in that they are largely objective, presenting ‘only a narrative of events, rarely offering much in the way of analysis’. Special Branch reports, in contrast, comment far more on the motivations of political groups, the GSC and trade unions, delineating the various political factions and commenting on the strategic importance of certain events.

For example, a Special Branch account of the ‘day of reckoning’ on 7 November 1977, carries a clear strategic understanding of the failure of the mass picket, predicting that this will lead to the defeat of the strike, ‘leaving the Left-Wing with the bitter taste of defeat.’ The Special Branch accounts can thus be read more like reports on how to break the Grunwick strike and the supposed positive political outcomes that will be achieved by doing so.

There is some direct evidence of collaboration between police and Grunwick’s management, including reports showing communication between coach drivers and police officers to facilitate entry into the plants. Members of the Grunwick strike committee and their supporters have claimed retrospectively that there was clear collusion throughout the mass pickets.

Some of the information from the SDS, other Special Branch sources and MI5 would have been extremely useful to the company. Most probably, it was relayed through the Industrial Desk at Special Branch set up in the late 1960s.

There is some circumstantial evidence for a transfer of information. For example, the ‘Pony Express’ operation organised by NAFF to remove mail from Grunwick was organised and executed almost immediately after a decision by the UPW at Cricklewood to extend their boycott of Grunwick’s mail.

The outcome of the UPW vote on the morning of 6 July only became known in the public domain the following evening, but Ward and the NAFF may have been primed by Special Branch, before the vote, and operation ‘Pony Express’ already enacted.

An overall view of the strike does indicate that the Metropolitan Police and Ward, the directors of Grunwick and NAFF, were always, it appears, one step ahead of the GSC and the trade unions.